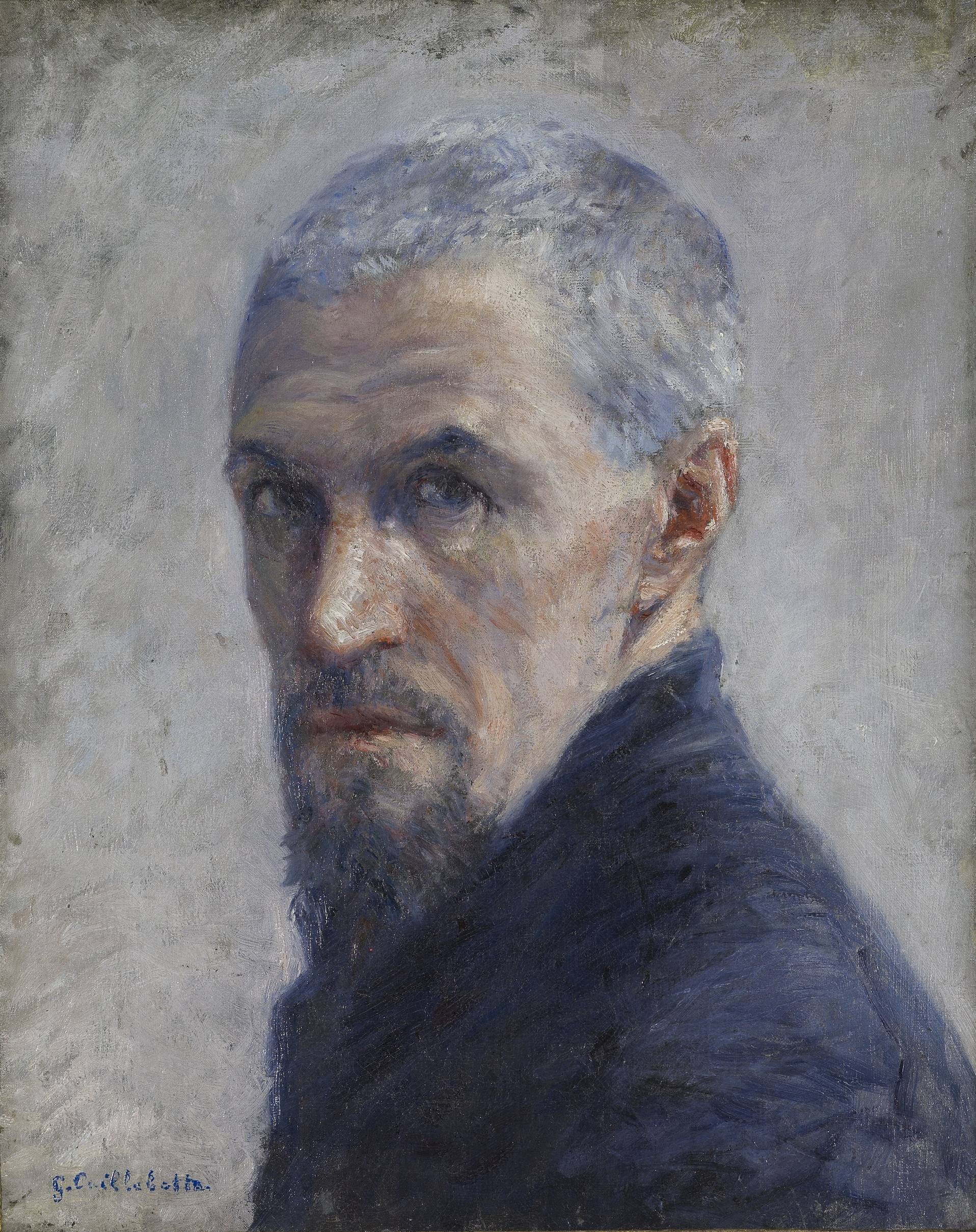

Gustave Caillebotte

(Paris, 1848 - Gennevilliers, 1894)

The work of Gustave Caillebotte, long overshadowed by his role as a patron, reveals a unique artist, inspired by the modern city and his own garden.

Painter of Haussmannian Paris

Gustave Caillebotte trained in the studio of painter Léon Bonnat and successfully passed the entrance exam to the École des beaux-arts. His father, Martial Caillebotte, died in 1874, leaving him a comfortable fortune.

After the refusal of his painting The Floor Scrapers by the Salon jury, Caillebotte got closer to the Impressionists and joined the group’s second exhibition in 1876. The same year, his brother René died at the age of 26 years. Gustave then drew up his will and made arrangements to bequeath to the French State the collection of impressionist paintings that he began to gather. His regular purchases from his friends were an important financial support for those who, like Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro and Alfred Sisley, could not count on a family fortune.

Paris was then a vast building site. Caillebotte, who lived in the new district of Saint-Lazare station, liked to underline the perspectives of the modern city, sometimes from the balconies which run along the Haussmannian facades.

The garden of Petit Gennevilliers

Caillebotte was a keen yachtsman. In 1881, he acquired a property at Petit Gennevilliers, on the shores of the Argenteuil basin, a famous pleasure boating spot at the time. He created a garden there, which gradually took a predominant place in his work. Like his friend Claude Monet, a few years later, he drew inspiration from this vegetal universe to imagine large decors, such as his Bed of Daisies, which remained unfinished.

His death in 1894, at the age of forty-five, interrupted a promising artistic development. The scandal surrounding the bequest of his collection to the French State soon overshadowed the originality of his work as a painter.

The Caillebotte bequest

After Caillebotte’s death, his brother Martial and Auguste Renoir, his executor, informed the authorities of the legacy he instituted: more than sixty masterpieces of Impressionism. The authorities hesitated. After two years of negotiations, forty works were accepted and exhibited in an annex to the Musée du Luxembourg where they caused a scandal. Impressionism was still far from being accepted by the art establishment. The collection is now in the Musée d’Orsay. It includes, among other exceptional paintings, Manet’s The Balcony, Renoir’s Dance at Le moulin de la Galette, Monet’s The Gare Saint-Lazare and his Regatta at Argenteuil.

The museum

About us

See more

The museum

The garden

See more