Painting en plein air

About

Preferred by Impressionists for its sincerity, plein air (outdoor) painting is the result of a long process during which the landscape became a separate genre.

The origins of plein air painting

From the 18th century, painters in France sought to observe the landscape, objectively making use of the effects of light. François Desportes, a painter specialising in animals in the court of Louis XIV, left us around seventy views of Île-de-France painted outdoors with oils. From 1708, the Landscape treaty by Roger de Piles advised painters to work outdoors. For all these artists, studying nature was a pre-requisite to creating a composed landscape, and sketches painted on paper were intended to be hung on studio walls as documentation for the painter, who drew inspiration to create a historic landscape.

Working outside the studio led to serious organisation problems, which would not be fully resolved during the Impressionist era. The artist had to carry around heavy kit, a parasol, folding chair, sheets of paper and a paintbox to their chosen site. They also had to work quickly, as nature is fleeting: the movement of a cloud is enough to transform the motif where the light changes and the shadows move as the time passes.

The English school of painting emerged from the second half of the 18th century, in a country at the precipice of an economic and industrial revolution. By isolating it partially from the continent, the wars against revolutionary France and the continental blockade from 1806 to 1814, encouraged the creation of national painting. From the end of the 18th century, English landscape art developed well beyond the inferior status to which it had been relegated by the traditional hierarchy of genres created by the Royal Academy. Outdoor painting became an essential principle for an entire generation of painters who strolled through the English countryside. Joseph Mallord William Turner and John Constable, in particular, captured the variety of nuances of the constantly changing British sky.

In Rome, from the 1780s, the practice of plein air painting experienced an extraordinary development. Artists from France, England, Germany, the Netherlands or Denmark underwent an academic education dominated by the ancient model. Deciding to study the monuments of the peninsula, they also discovered the city, its gardens and the surrounding countryside. Impressed by the light which they had previously ignored, from the early 19th century the painters tended to reflect nuances on the canvas.

From Rome to Barbizon

In 1825, the young Corot left for Italy, where he stayed for nearly three years. Shortly after his arrival, he set a target to paint every day on the Palatine, working on one study in the morning, another at noon, a third in the evening, anticipating the “series” painted by Claude Monet. Unlike most of his predecessors, Corot did not stop painting en plein air when he returned to France in 1828. He went outdoors regularly and found inspiration in Paris, Île-de-France, Burgundy, Normandy, the forest of Fontainebleau, etc.

From 1835, Théodore Rousseau became the leader of the Barbizon painters, where he chose to paint nature without making reference to history. For him and for Corot, painting outdoors was a preparatory stage for depicting landscapes created in the studio. Charles-François Daubigny travelled to Italy in 1836, but it was an initial stay in Barbizon in 1843 which truly changed his art. From this point, he opted to observe nature and chose to depict its most fluid aspects, like lakes and rivers. To get even closer, he created a floating studio, the Botin.

The changes in equipment available to painters, and notably the sale of paints in tubes, made outdoor work even easier. During the day, artists painted studies outdoors, which were completed in the evening in the studio, and often mounted on a canvas later. Gradually, this work stopped being a simple stage of the creative process and many exhibited studies presented as independent works at the Salon des études.

Birth of Impressionism

A native of Honfleur, Eugène Boudin did not receive a classical education. He learned by observing the paintings of ancient and contemporary painters and above all, by working outdoors. For him, nature was the “grand master”. To capture the changing sky of the Seine estuary, Boudin developed a rapid technique and opted for small formats. This style of painting and his desire to preserve his first impression – the most important for a painter, in his opinion – led him to blur the lines between sketch and completed painting. He became one of the first to elevate a study to the level of artwork in itself. Critics often mentioned the lack of finish in his pieces, but his example left a deep impression on the work of the Impressionists.

Édouard Manet painted his life studies from 1853 in Normandy, but like Edgar Degas he was uninterested in landscapes, except for seascapes, a category he wanted to renew. During the first years of Impressionism, he painted On the beach (Paris, Musée d’Orsay) in 1873, which contains sand mixed with the paint, proving the artist worked in situ.

Berthe Morisot was a student of Corot and he got her to paint outdoors. Her brother Tiburce described her as “wearing a backpack, tool in hand, with all the kit of a landscape artist, she disappeared for whole days, going to the cliff from one motif to another depending on the time and angle of the sun.” Paul Cézanne worked on landscapes in the countryside of Aix-en-Provence from summer 1862. From 1872, Pissarro worked outdoors with Cézanne near to Pontoise. Snowy landscapes around Louveciennes painted directly on canvas during the winter of 1870 in the company of Monet are some of the first masterpieces of the Impressionist school.

Of all of them, Claude Monet was the most stubborn about working outdoors, and his correspondence clearly demonstrates the difficulties he encountered. During the 1860s, he worked with Frédéric Bazille in Honfleur and they both met Alfred Sisley in the forest of Fontainebleau. When he painted Camille on the beach at Trouville in 1870, he started painting on his canvas outdoors, and did not try to hide the grains of sand encrusted in the colour. The air circulates freely around the figures, and the artist was able to translate the freshness of the day and the brightness of the seascape. Impressionism was born.

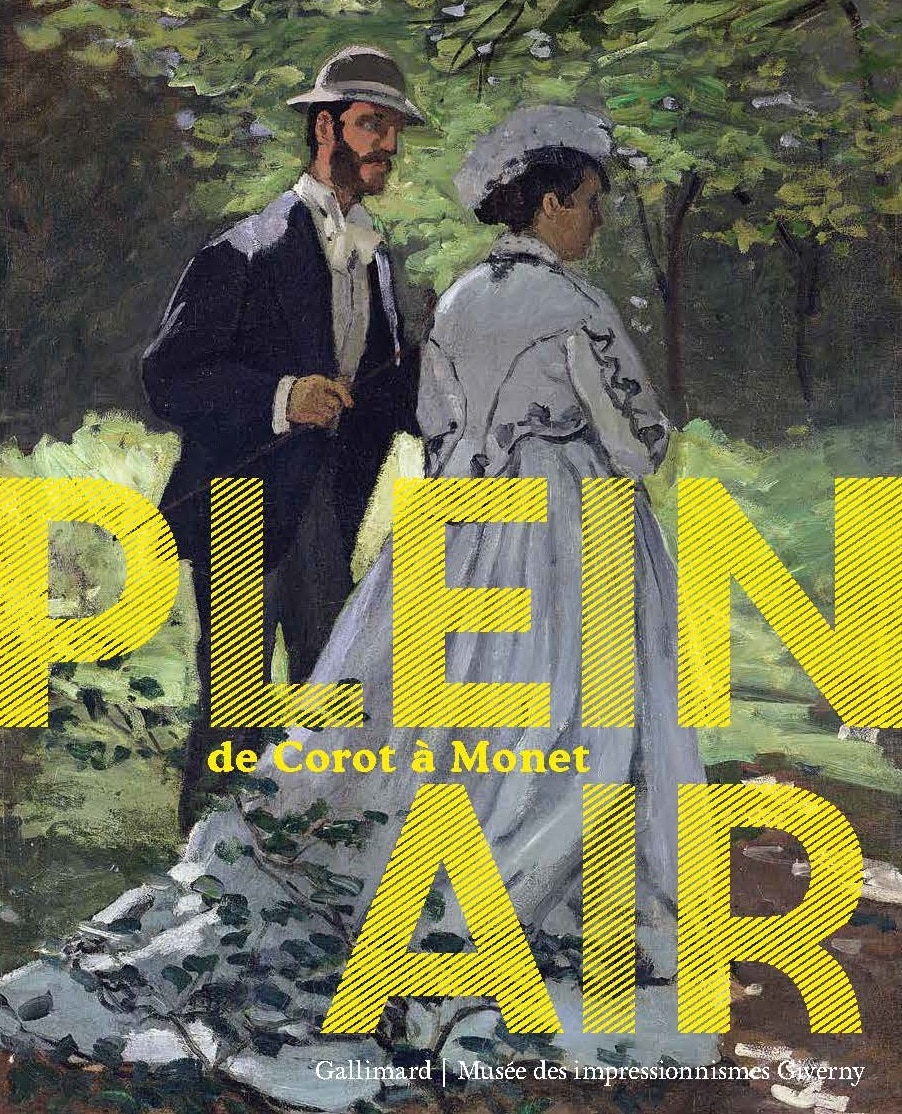

The exhibition “Plein air. From Corot to Monet”

From 27 March to 28 June 2020, Musée des Impressionnismes Giverny was supposed to present the exhibition “Plein air. From Corot to Monet” and allow its visitors to return to the roots of Impressionism. The exhibition would have told the story of plein air painting, from the 18th century until 1873, the year preceding creation of the term “Impressionism”. From travelling artists to the first Impressionists, plus the Barbizon School, one hundred pieces by Joseph Mallord William Turner, Camille Corot, Eugène Boudin, and even Claude Monet should have been exhibited. In accordance with government restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic in France, the exhibition “Plein air. From Corot to Monet” had to be cancelled.

The exhibition “Plein air. From Corot to Monet” was organised by the Musée des Impressionnismes Giverny, with the tremendous support of the Louvre Museum, Paris, Musée d’Orsay, Paris and the collaboration of Istituto Matteucci, Viareggio.

L’exposition s’inscrit dans le cadre de Normandie Impressionniste 2020.

In images

Zoom on the works

Patronage

Our patrons

The museum warmly thanks the patrons of this exhibition.

The museum

About us

See more

The museum

The garden

See more